| |

| Purveyors of Fine Fantasy and Science Fiction . . . and More! | |

|

E-mail us at information at callihoo.com |

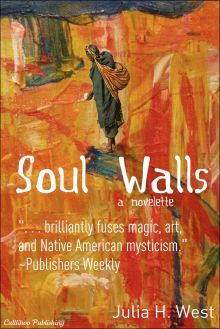

Soul Walls (sample)

Soul Walls (sample)

Julia H. West Originally printed in Marion Zimmer Bradley's Sword and Sorceress XXIV, edited by Elisabeth Waters, Norilana Books, November 2009. buy (epub) buy (mobi) Tiva and the other apprentices sat cross-legged on mats in front of Yongosona's house, eating rolled corn cakes and enjoying the dawn breeze teasing the mesa top. Behind them the sun rose, its rays painting Red Cliff, far to the west. Already the air was hot, and they'd been up since before dawn, plastering the wall at Chumana's house, so the breeze was doubly welcome. Yongosona, their teacher, pushed the woven door hanging aside and stepped out into the sand outside her door. She was an old woman, the oldest Tiva had ever seen—wrinkled and stooped, her hair wispy as summer clouds—but was still bright of eye and steady of hand. Her fingers, tunic and skirt were all daubed with the paints of her profession. Paints, Tiva thought in dissatisfaction. I run half a day to collect materials for them, I grind them, I mix them—but I never get to use them. "Today," Yongosona said, "we paint Chumana's Soul Wall." Tiva glanced up at her teacher. Yongosona usually did not say 'we' when she spoke of painting. Would she allow one—or several—of her apprentices to aid her in more than plastering walls or mixing paint this day? Tiva pushed the rest of her corn cake into her mouth, dusted her hands off on her skirt, and rose to her feet. The other apprentices also stood, from Honovi—already a woman and looking forward to when her own Soul Wall would be painted—to little Pamuya, who was in her eighth summer and had come to Yongosona at winter's end. Yongosona gazed up at the girls for a long time, never blinking. Her gaze was distant; she was thinking of the Soul Wall to be painted. Finally she said, "Honovi, bring the gold earth and the white. Tiva, the most brilliant red and the black. Kawaina, all the greens. Lomahansi, the light blue…and the jewel blue. Pamuya, carry the basket of brushes and scrapers." The girls scrambled into Yongosona's house. The inside back wall was covered with shelves which held pots and carved stone boxes, and pegs from which baskets and tight-woven bags depended. By now all the girls, even Pamuya, knew exactly where every piece of Yongosona's equipment belonged. Tiva took down the pot of brightest red paint. She lifted the lid and peered inside. There was little left—Yongosona had used much bright red in the last Soul Wall. Maybe that would be enough; it seemed this wall would have much green and blue in it. She put that pot and the larger one of black paint in a small basket, padding the pots with straw so they wouldn't strike against each other and break. Usually she had much more to carry. Yongosona always took an apprentice with her when she painted a Soul Wall, but most of the girls were sent off on errands, or stayed at Yongosona's house making paint. Excitement rose in Tiva's chest. They were all going today! The girls followed their teacher along the plateau, through sandy lanes between attached houses plastered in brown, cream, and red. Chumana's brothers and other kinsmen had just finished adding her new home to her mother's, and were plastering it in the same warm orange-red shade. The men stopped their work and stood aside, nodding and murmuring "Grandmother" as Yongosona and her apprentices passed into the house. It did not have a door hanging yet; that was still on Chumana's intended husband's loom, a day at least from completion. Tiva, standing in the doorway, saw a half-grown boy, Chumana's brother, run into his mother's house. Moments later, Chumana and her husband-to-be came out, faces shining with excitement. Chumana carried an armload of cushions; Honovi accepted one from her and helped Yongosona to seat herself cross-legged on it, then the apprentices all lined up behind their teacher, still holding their burdens. "Esteemed elder," Chumana said, touching her forehead at Yongosona. Mikwliya, her husband-to-be, echoed her. "Sit." Yongosona motioned to the floor in front of her. They dropped cushions and sat before her, side by side, shoulders touching. Yongosona reached out, the loose sleeves of her multi-colored tunic falling back as she spread her fingers and rested them on the foreheads of the young couple before her. All three closed their eyes. Tiva quietly pulled the straw from the basket she carried. Beside her, she felt Honovi doing the same. They never knew how long this part would take, but when Yongosona asked for paint it must be ready to set into her hand. Yongosona took a long time. Pamuya fidgeted, shifting her weight from one foot to the other. Yongosona's arms were shaking now, and sweat ran down the faces of the young couple. Yongosona began to hum, a monotonous up-and-down sound. Tiva wished she knew what Yongosona was doing. Somehow, she was discovering what to paint on the Soul Wall, but she would never tell her apprentices how she knew. Was it something only in her mind? Did a god tell her? How could Tiva ever paint Soul Walls if she never got to paint and didn't know what to paint? Abruptly Yongosona dropped her arms and opened her eyes. "Go," she told Chumana and Mikwliya. Chumana—only two summers older than Tiva—staggered to her feet and pulled Mikwliya up with her. Without a word, they left the house. Tiva and Honovi helped Yongosona to her feet. The old woman took a paintbrush from the basket Pamuya held and stood surveying the wall they had prepared that morning, blank white. She gestured with the brush, then said, "Red." Tiva took the lid off the red pot and placed it under Yongosona's brush. What did the old woman see as she surveyed the unblemished wall before her? Did the painting live behind her eyes, merely needing to be copied onto the surface? And how had she known before she came what colors she would need? One long curving line, then another, red on the white surface. Then, "Black." Tiva held out the other pot, and Yongosona took another brush from Pamuya. Tiva watched carefully. She knew that at this stage in Yongosona's Soul Walls there was no discernable design. Tiva couldn't look at a section and say, "This will be a spine tree, this will be a gazelope." But later, when it was nearly finished, all the various parts came together, and she would be able to see that this black line was the gazelope's hip, and that brown one traced an eagle's wing. Today, it seemed, Yongosona would tell them what her lines meant. She began to murmur as she painted, and Tiva had to listen hard to understand. "Swiftness for their children, like the sandrat over the desert," she said as a line in gold earth, then a few more, became a sandrat's supple length. Tiva's heart began to pound. Yongosona was explaining what she painted! She had done this seldom since Tiva became her apprentice. The other girls didn't seem to notice. They held paints for their teacher and Pamuya clutched used brushes. They fidgeted and yawned as the painting grew before their eyes and Yongosona's voice, quiet as a breeze, described sandrose and corn stalk. Then Yongosona said "red" once more, but instead of dipping her brush into the pot, she squinted at it. "Not enough brilliant red," she said. "Need more tomorrow." She looked up at Tiva. "Go to Red Cliff now. Get the brightest red earth." She turned away from Tiva, asked for green, took another brush, and traced a line—part of a cornstalk—close to one of earth gold. Though she wanted to stay and listen to Yongosona's explanations, Tiva set her pots down next to Honovi and ran out the door. She held her hand up to gauge how high the sun stood above the village. It was already a few handwidths above the horizon. Red Cliff was half a day's run away, and after she gathered the earth she would need time for grinding and mixing the pigment. She must make the most of the daylight. She hardly paused when she reached Yongosona's house. Food bags hung, already filled, on their pegs. Water bag here, basket for the earth she would collect here. Already on the run, she dropped the bags into the basket and left the house's dark coolness for sunlight as she settled the basket on her back. The path from the mesa to the desert below was steep and zigzagged down the cliff side. But the men and boys who ran it every day to get to their fields below had pounded it hard and smooth with their feet, and Tiva sped up. She was getting her stride now, and only slowed a little at each turn for the next long downward slant. She ignored the dizzying drop an arm's length to one side. Red Cliff, as far west as Tiva had ever been in her sixteen summers, was the western border of the land claimed by Tiva's village, Ayantavi. They shared it with their neighbor to the north, Shokitevela. The boundaries had been negotiated between their Talker Chiefs generations before, since both villages obtained earth for pigment at Red Cliff. When she reached the desert floor, Tiva settled into a steady pace, running with a long stride. She had learned that if she tried to run fast, she just tired herself. So she ran, her face toward Red Cliff, her thoughts wandering far from the desert she traversed. Yongosona would not let her paint, but that did not mean Tiva did not paint. Red Cliff had many caves and there was one—far up the cliff, a hard scramble—where she had smoothed and plastered the wall and sometimes tried painting for herself. But her lines were wobbly, and no matter what curves and lines she added, she rarely saw a plant or animal. She had plastered over many attempts, but was beginning to think she would end up like many of Yongosona's other apprentices. She would find a nice boy in another village and bring him home, and Yongosona would paint them a Soul Wall, and she would turn to decorating pottery or making patterns for weaving. Red Cliff was closer now, and Tiva sipped from her water bag, never breaking stride. She adjusted her headscarf so the sun, directly overhead, wouldn't burn the back of her neck. The basket on her back was beginning to chafe through her sweat-damp tunic. When she stopped, she'd adjust it. The desert, under the mid-day sun, was quiet. Animals were smarter than humans, and hid in their cool dens when the sun was fiercest. Always running, breathing deeply but without panting, Tiva surveyed the area. Yellow sand everywhere, dotted with grey-green brush, and now and then a darker rock poking through. Nothing moved, no breeze stirred the sparse branches; even the dust of her running sank almost immediately. She was alone with her discontent. Yongosona had been explaining today, had told them things as she worked. Usually she merely grunted words—requesting paints, brushes, or other materials. What were the others learning while Tiva was off gathering earth? In eight summers of helping Yongosona, Tiva could count the times when the old woman had explained her paintings on the fingers of one hand. Yongosona taught them to make the materials, and then bade them watch and think on what they saw. Tiva watched, and Tiva thought. But she had not learned how to paint. She had not learned what made a Soul Wall the heart of a home, and not just a decoration like she could paint on a pot. "You run well, girl," said a voice close to her ear. Almost, she broke her stride. Almost, she stumbled. But she caught herself and stared, open-mouthed and startled, at the young man running beside her. He must have been resting in the scant shadow of one of the rocks, or she would have seen him earlier. Now he paced her easily, running alongside and grinning at her shock. "Thank you," she said finally. "I have far to go." "You do," he said, his words smooth, his breathing easy, though he ran as swiftly as she. "May I run with you?" His face had a familiar look to it. Like the runners in Shokitevela, he had his waist-length hair tied with a cloth striped in red and yellow, but his trousers and tunic were white, not bright colored as most men favored. Perhaps she had seen him before, at the races with Shokitevela last fall. There should be no harm in his running alongside her. "If you wish," she answered. They ran together, the only sound their sandals swishing through the sand and the slight huff, huff of their breathing. Soon the young man's silence began to disturb Tiva. Why did he want to run with her, if he had nothing to say? Did he wish to spy out where Ayantavi got their colored earths, to take them for his own village? Men did not paint, but they did weave, and the brilliant red earth would color his yarn far better than the faded red in his head-cloth. She began to regret allowing him to run alongside her. "Sensing souls is difficult," he said, startling her from her uneasy thoughts. "Yes," she said, to cover her renewed shock. "I…I don't know if I have the right soul to sense those of others." Why had she told him that? It was her most private fear, one she had told no one else, and now she had blurted it to a stranger. Cover design by Danica B. West, composited and photomanipulated from (background) Cliff Face by Steve Johnson, http://www.flickr.com/photos/artbystevejohnson/4592075150/ used under Creative Commons license, (figure) Hopi woman, Moki pueblo, Arizona, ca. 1902, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hopi_woman,_Moki_pueblo,_Arizona,_ca._1902.jpg, public domain. To read the rest of the story: Purchase from Callihoo Publishing (epub) Purchase from Callihoo Publishing (mobi) Purchase from Amazon.com: Other stories by Julia H. West from Callihoo Publishing: An Old-Fashioned Christmas Tree The Peachwood Flute (collaboration with Brook West) Weeds (collaboration with Brook West) |

| Banner by Danica B. West

This page created 22 September 2011 Last update 21 March 2014

|

|